FAS: You said you don't have much time to change your mind when you're out in the field. Don't you ever feel rushed and too pressured to work well?

FM: If an editor sends me two thousand miles to do a series of drawings of, say, a political event, that's what I've got to do to the best of my ability. I can't get there and decide that, that day, I would rather draw a bowl of flowers.

FM: I feel that the artist-reporter faces more of a challenge than the artists who pursues his own ends in a studio. But he is rewarded too. I think you gain from the interaction, from the pressures and the excitement. It doesn't lessen the art. It adds a dimension of immediacy.

FM: Working, at the moment, you feel an interplay of attitudes, your own and those of the others involved in the action, and you see it from several sides. The artist-reporter - and I would define myself as an artist who is involved with the events of his time - not only sees, but he interprets.

FM: He gives an event meaning by seeing it from another dimension, somewhat as a cubist painter works. He can see around corners of time as well as space, to give his picture depth as well as significance. The artist-reporter can do most of the time what only the best photographers can achieve sometimes. He can look behind and ahead of an event for its meaning.

FAS: Your work proves how immensely valuable the artist-reporter can be when he covers events. Yet most magazines and newspapers still rely on photography more than art to capture the happenings that make history. Why hasn't the artist had more impact on reportage?

FM: I don't want to give the impression that I'm arguing that the artist's coverage of an event is superior to the photographer's. They're entirely different and both of them have their merits. The editors don't really understand what the artist can do for them. In the publishing field they tend to see things as photographically interesting. When the Alabama police turned the hoses on those racial demonstrators, it made a terrific photographic image.

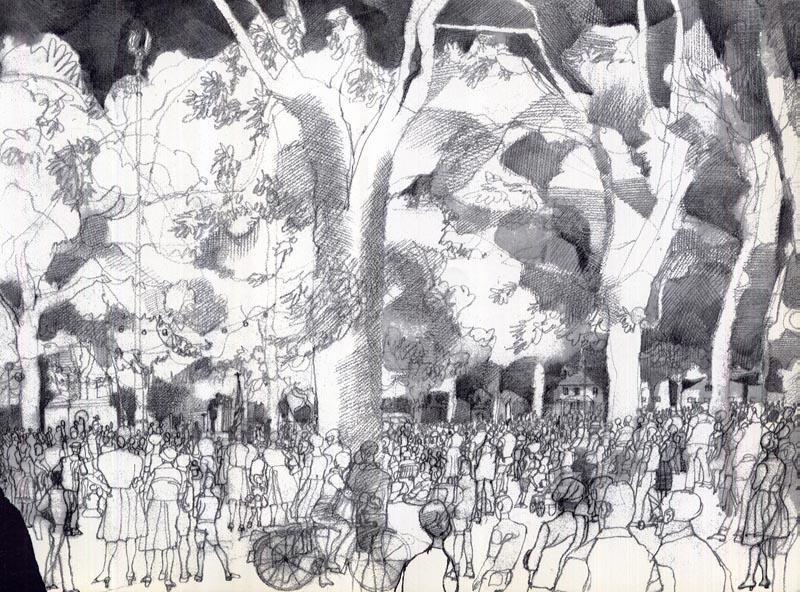

(Below: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking at a suburban rally in Winnetka, Illinois)

But the photographs didn't tell the whole story. They didn't tell what kind of people they were, how they got there, where they were going. This is the kind of thing the artist can do.

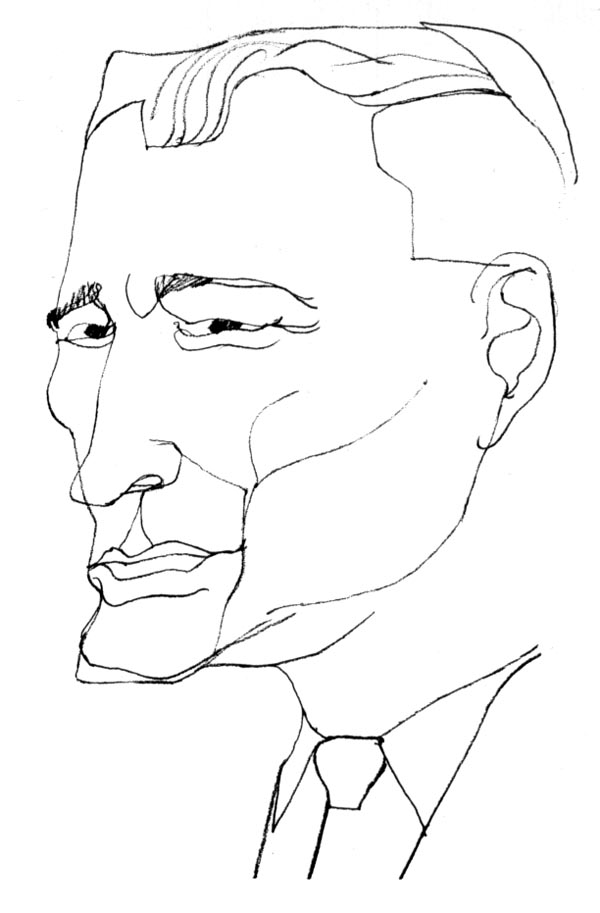

(Robert Shelton, Imperial Wizard of the KKK, drawn in Birmingham, Alabama)

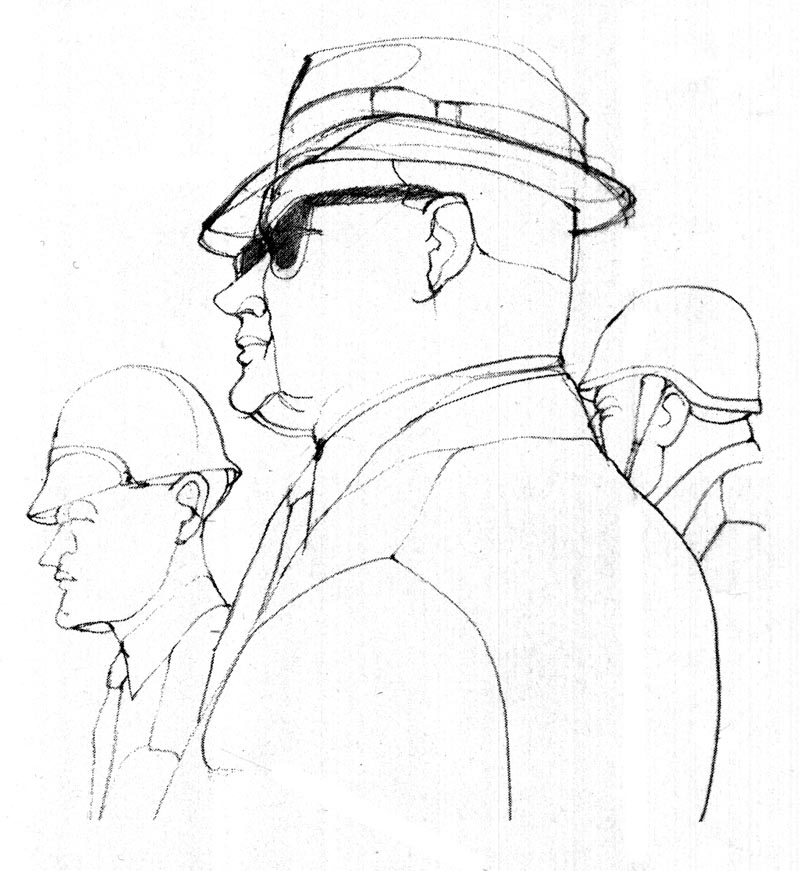

(Dallas County sheriff, James Clark, drawn in Selma, Alabama)

FM: However, these possibilities haven't been recognized by artists, so they haven't been recognized by editors who buy their work. There is a photographic approach and an artist's approach. It's not so much a question of the artist going against realism as it is of heightening the reality. There is a second look, a different look, which the artist can pull out of the story. The artist can get into the minds of people. He heightens the color, makes the story sharper. This is the excitement of art.

(Father Maurice Ouellet, former pastor of the "Negro" Catholic Church in Selma, whom McMahon interviewed during the demonstrations, and the first white man involved in the voter registration drive. He was subsequently transferred.)

FAS: Someone once said that you put that "extra dimension of meaning" into your pictures. Is that done consciously or is it simply the natural outgrowth of an artist's view of life?

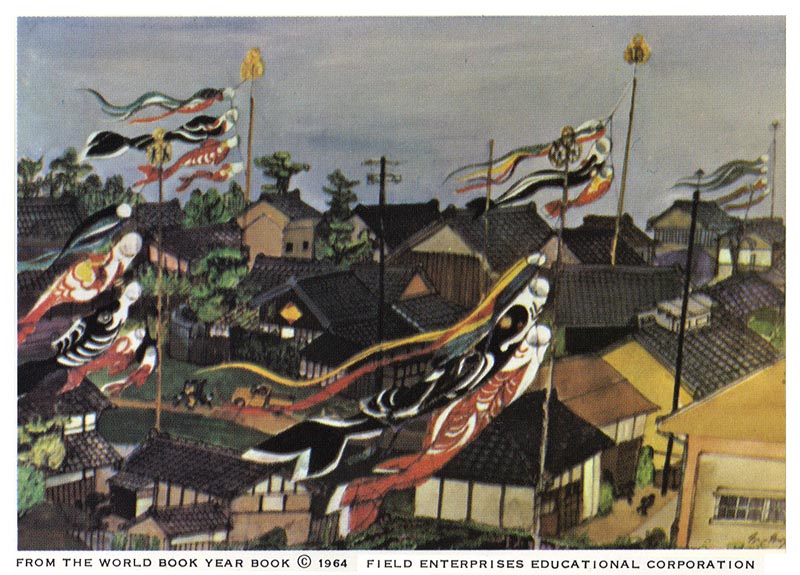

FM: What I look for is a symbol, the significant detail that will tell the story. When I did a picture of Japan's Boy's day I noticed all the carp flags flying. It's a day when they celebrate their sons. Every family flies cloth carp flags from their roofs, one for every son. So I let the flags dominate the picture.

FM: When I was doing my Ecumenical series in Rome I noticed a TV set on a Doric column, suggesting the changes in the Church. I put that in the drawing, of course.

(Below: McMahon's Ecumenical series)

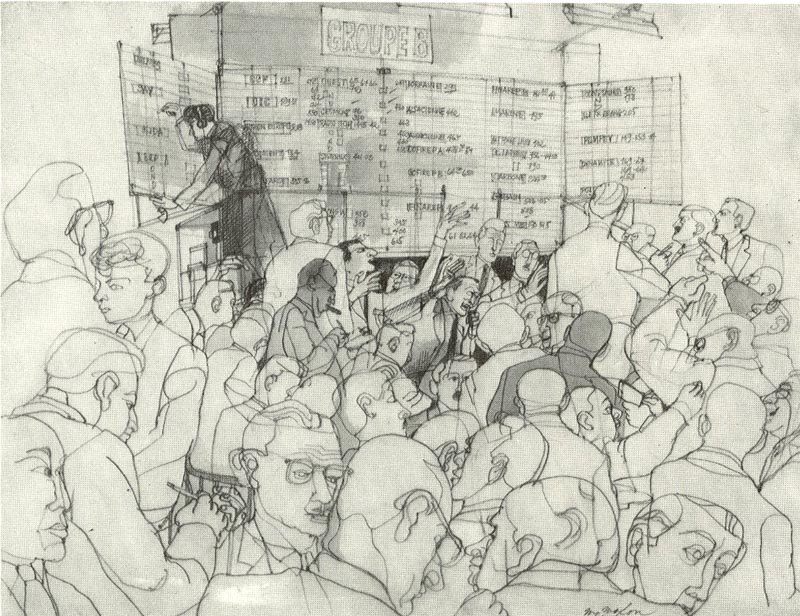

FM: When I did a meeting of Common Market officials I drew a tangle of wires which linked each delegate to his colleagues by way of the translator's booth.

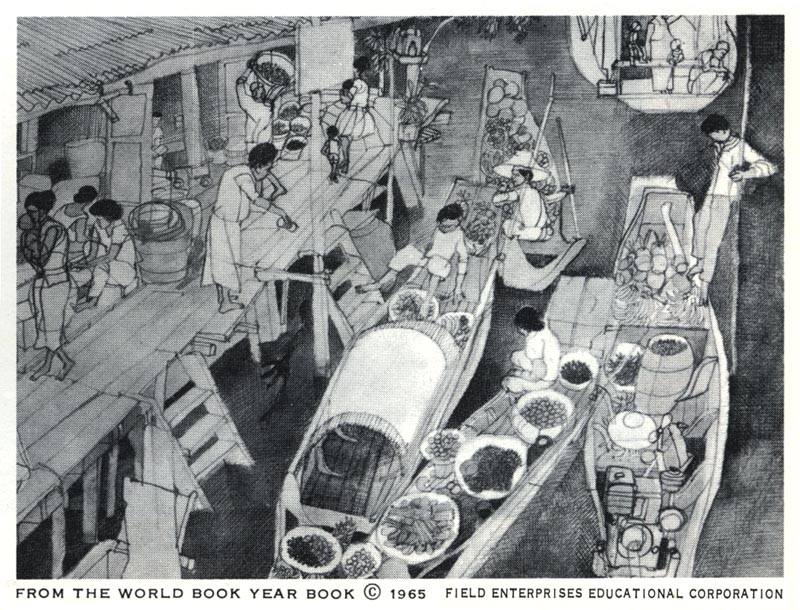

(Above and below: two pieces from McMahon's Common Market series)

When I drew an Asian priest I put in an electric fan right up front in the picture to show how hot it is in that part of India. What I'm trying to do is present the truth through this added dimension of seeing. Not all editors will go for that. They'll complain, "But this is interpretive!" And of course it is. But I think you can convey more "truth" this way than you can with photographs.

Take the drawing I did of a Japanese family in the living room of their home. The room has the traditional tatami floor, but a television set I noticed there suggets to me that even in a traditional, tightly structured Japanese family there is awareness of the outside world.

When I did a drawing of Adlai Stevenson I showed him as a private man, sitting at a cluttered desk. Books filled the wall behind him and nearby were pictures of his children and Abraham Lincoln. I was interested in Stevenson the thinking man. This is the way I saw him, alone and thoughtful, among things he loved. A photograph might have recorded the scene, but the details could not have been given the same emphasis.

* Concluded tomorrow

* Many thanks to Matt Dicke, who provide all the material for today's post.

Post a Comment