FAS: You cheerfully admit that even when nobody asks you to cover a story you go ahead and make the drawings and then, hopefully, find someone to publish them. Do you like working on speculation?

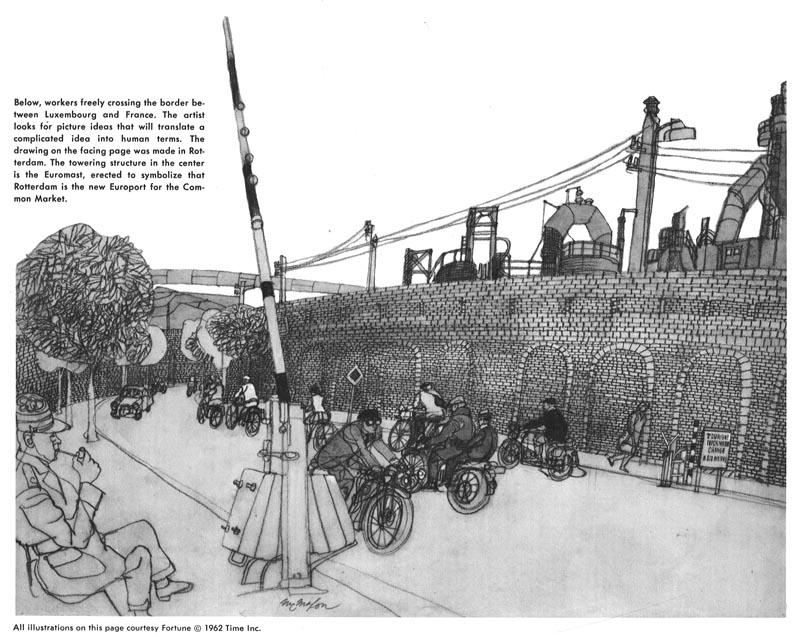

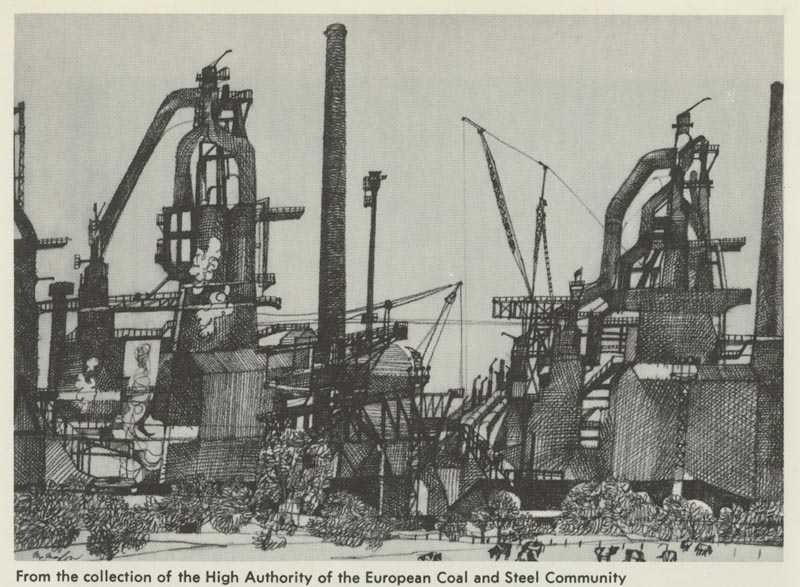

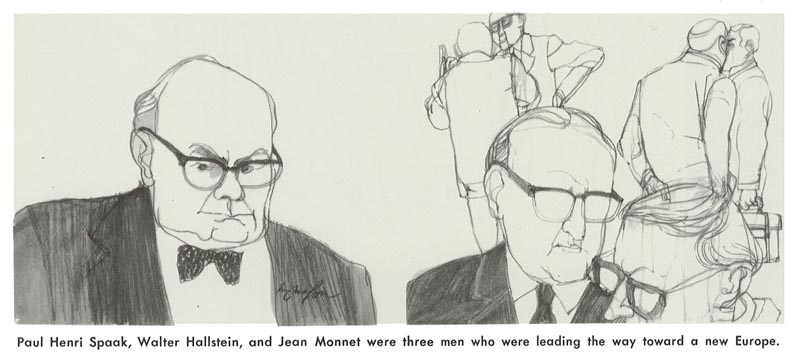

FM: I query somebody when I have a good idea or I go ahead and find a place for it later. Nobody gave me an assignment for my Common Market story, which I sold to Fortune.

(Below, McMahon illustration from his Common Market series for Fortune magazine)

The reason you go ahead is the possibility of a big exciting payoff if you keep your eyes open. Timing is important. An editor may tell you, "We're not doing that kind of story." What he means is, "We're not doing it this week." But his interest could develop. After the second or third look he may want the story. Particularly when the subject has been exhausted and a new look is needed.

FM: The magazines can do stories to illuminate a subject before it becomes a problem and even anticipate the headline. I suggested to a magazine that they do a story on what the people of Birmingham were thinking long before they turned the hose on them.

FAS: Why don't magazines take more of a chance?

FM: An editor doesn't know what's out there. Neither do you until you get there. That's why you have to go and find out. When you get there the story begins to turn over, but sometimes not until you're in the middle of it. I'm not talking about exposés. The artist can celebrate the things that are positive. It's a question of the artist interacting with a meaningful subject, something that interests him.

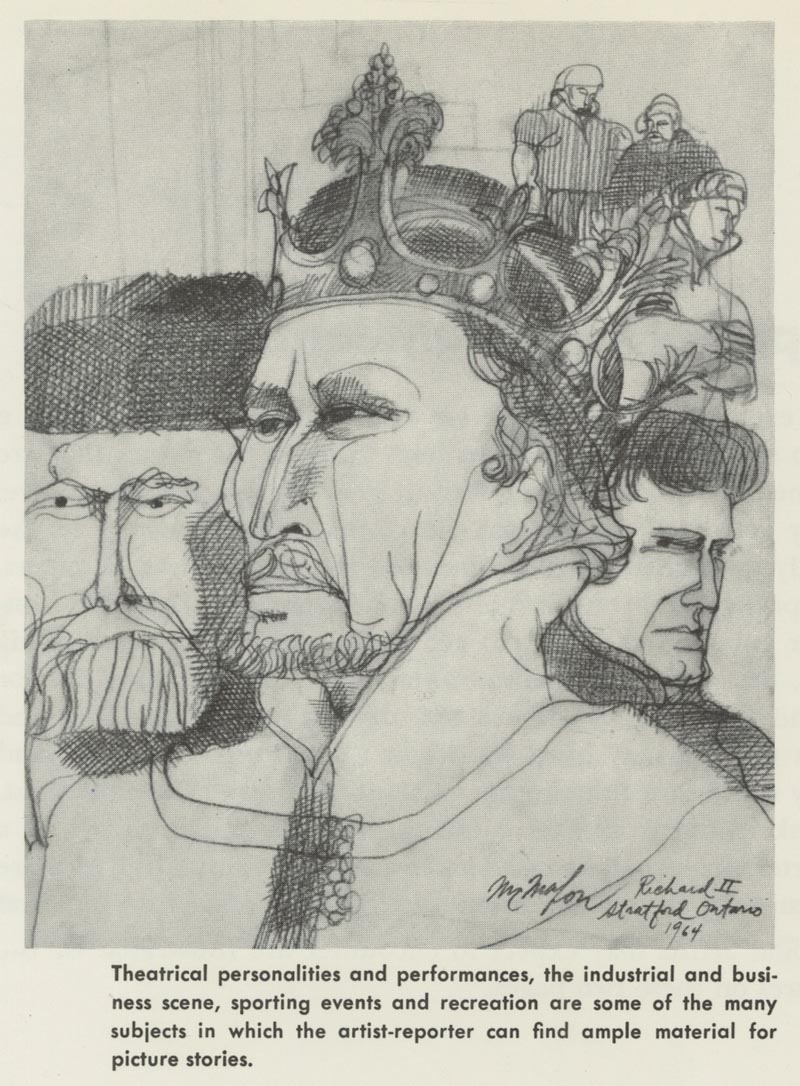

FAS: What interests you?

FM: One thing that interests me is civil rights. The Vatican Council and the way it relates to civil rights, non-violence, which seems to be the major theme of our times. It's what the young people in the streets are thinking about. I don't think Churchill is really the man of the century. Probably Gandhi.

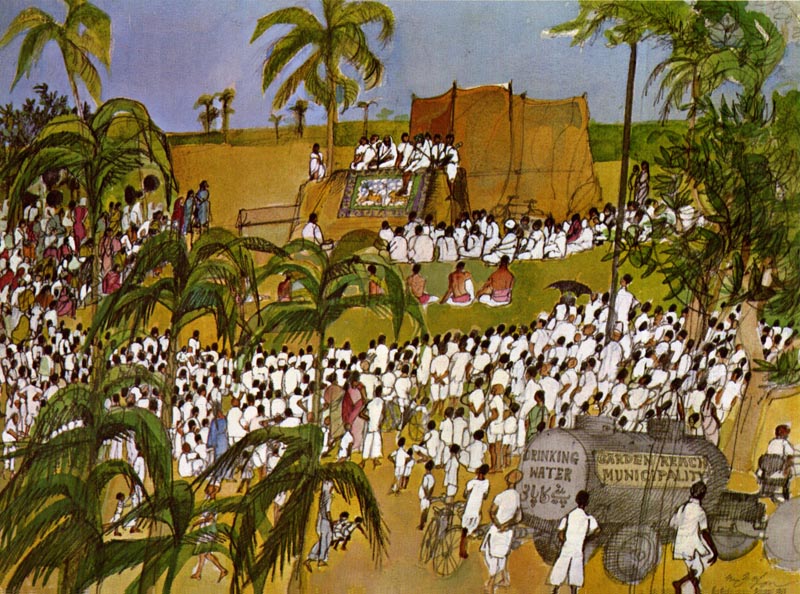

(Below, a crowd in India listens to Vinoba Bhave, Fortune magazine, 1963)

FM: I'm interested in the changes taking place in the established church. What goes on is so much conditioned by the relationship of Christians to Jews. The Ecumenical movement, bringing people together, becoming a world society - these are the kind of things that interest me. My first consideration is to do stories that interest me and then do them so they are published.

FAS: How do you develop a reporter's eye?

FM: Keep your mind open. I think there's a story everywhere. There are certain visual ideas, reportorial ideas, actually, that are best expressed in art. There is no way of knowing what ideas these are until you go out and look around.

FAS: When you go out after stories that interest you, do you go out with an attitude, an editorial point of view?

FM: If I have an attitude, I would like to stop having it. When you start out on a story you probably do have some preconceived idea of what you will find. but going there changes your idea of what a place is like. What you suddenly realize in Selma, for example, is that this is a condition of humanity. There are good people on both sides who want to work it out and bad people on both sides. All your notions are scuttled because you are dealing with human beings and not symbols.

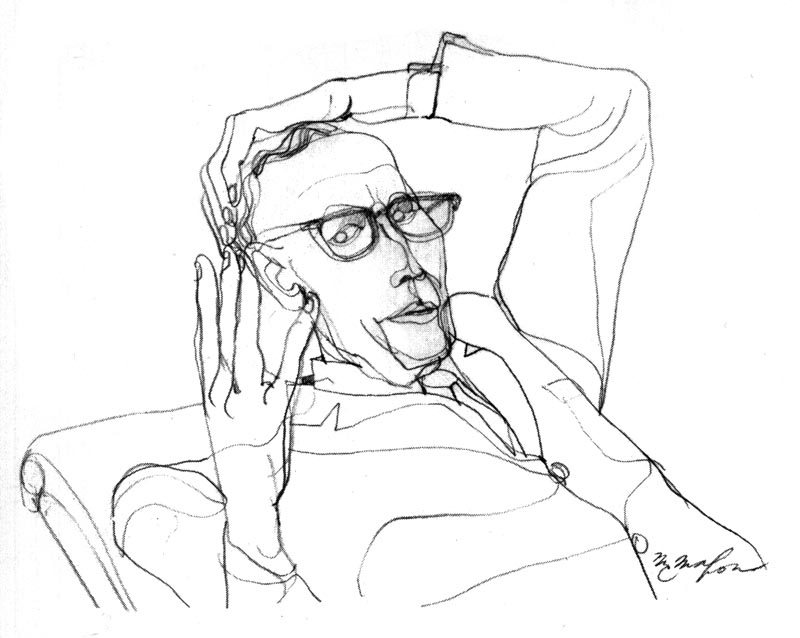

(Below, the head of the Chamber of Commerce, Birmingham, Alabama)

FAS: You seem to have no trouble getting into conventions, conferences, going where the action is. How do you get in? What kind of accreditation do you need?

FM: You have to look for the public relations guy and explain what you want to do. the artist is unique, and there is no machinery set up to accommodate this. usually there is a man who handles writers, and one for photographers. At political conventions I go to the press guy who deals with writers. When I was doing the Common Market story and I wanted to interview Lord Hinchley I called the headquarters of the Conservative Party and explained what I wanted to do and the press man called him and arranged it. Most people want to get their ideas across and you can help them do it. There's no reason why they shouldn't welcome an artist. The only problem is finding the right contacts.

FAS: I notice that you not only describe yourself as an artist/reporter, but you also volunteer to do the text for a drawing and make layouts for the project you're working on. Your training must have been very comprehensive. Was it?

FM: I went to the Chicago Art Institute, the Institute of Design in Chicago and WPA art classes. I went mostly at night because I apprenticed in an art studio as soon as I got out of high school. The WPA sessions were simply life classes. I studied painting and materials at the Art Institute. Chicago is a design center in the sense that the artists who work there have a primary interest in developing their pictures for printing. You take a thing from the start. You aren't called in at the end. When I did something for an agency I wanted to do the layouts too. The total thing.

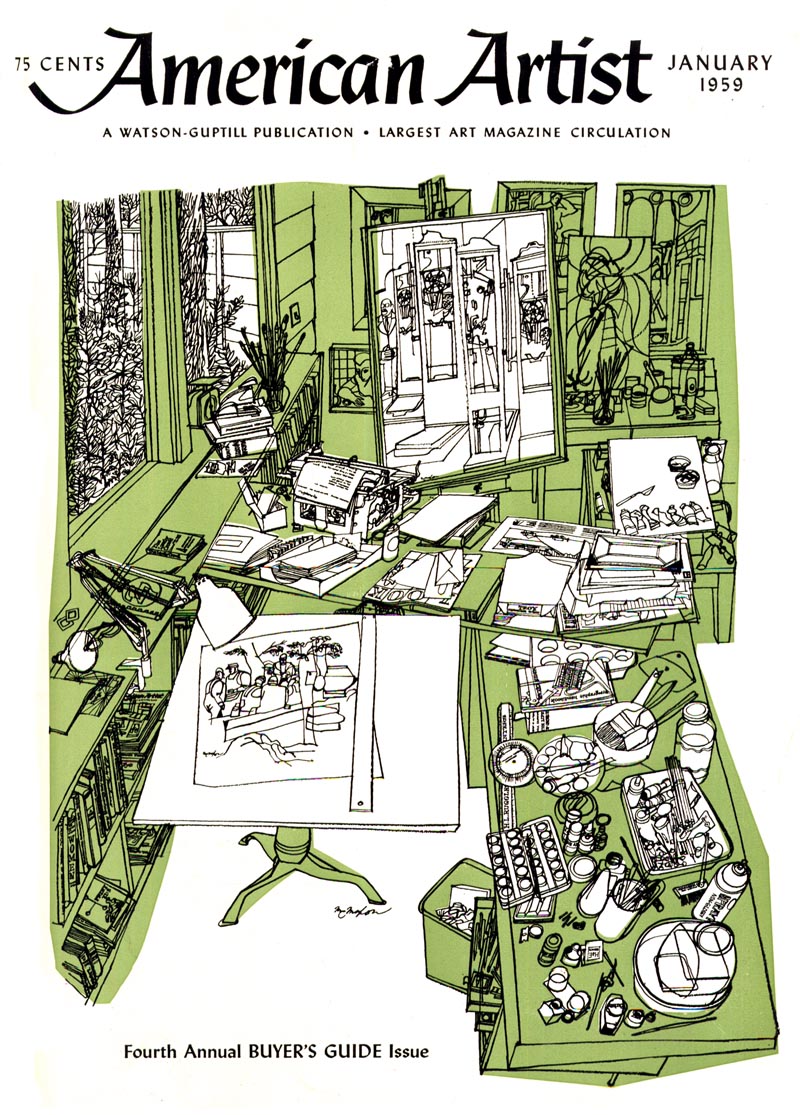

FAS: Where do you work when you are not out on location?

FM: I have a studio in my house and one in Chicago. Increasingly, I work at home. I have a small office in Chicago which I share with a designer.

FAS: When did you really begin concentrating on reportage?

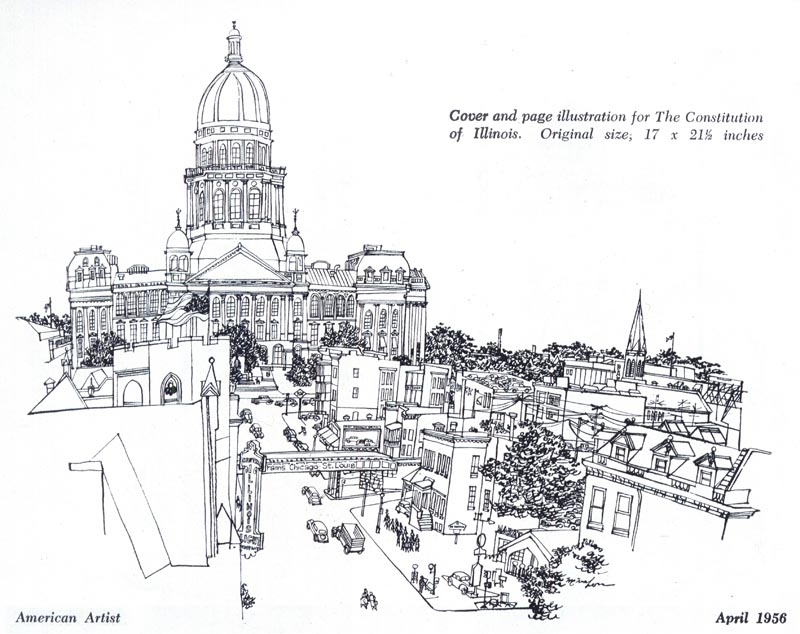

FM: Around 1955, when I decided I was spending too much time in the studio. The first chance I had to get out came when I was offered a job illustrating a book on the Constitution of the State of Illinois. Rather than doing a kind of organization chart with drawings showing what the Legislature did and the Governor did and so on, I proposed that I would go out into the state and see how the people lived under this Constitution.

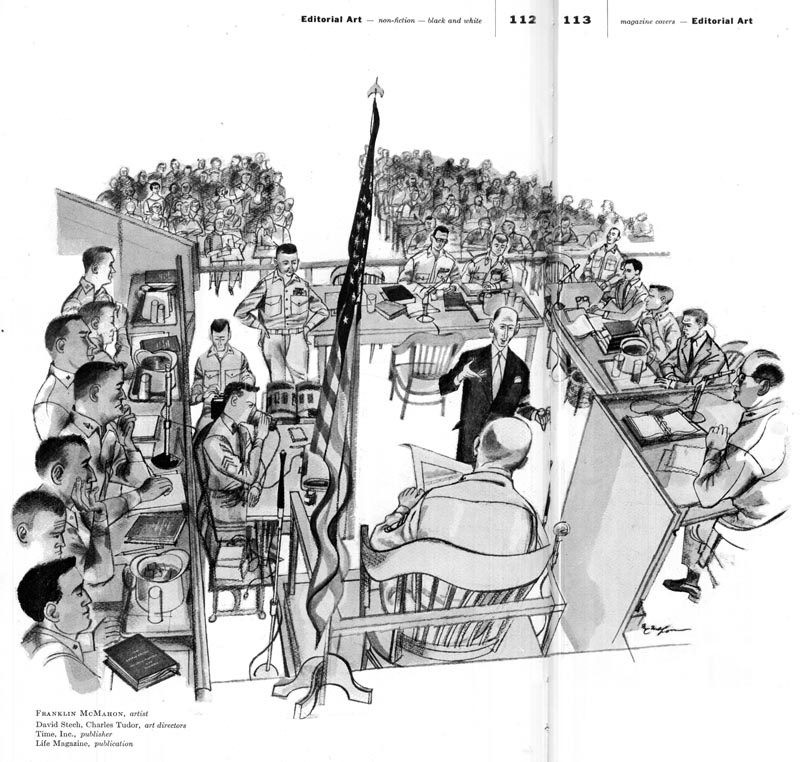

The effect of the laws on transportation in a small city, for example. In a way, what I was doing was decorative art because the pictures could be used anywhere in the book and did not specifically illustrate a given piece of text. I sent the book to Life as an example of the kind of work I wanted to do and they gave me an assignment to cover the Till trial.

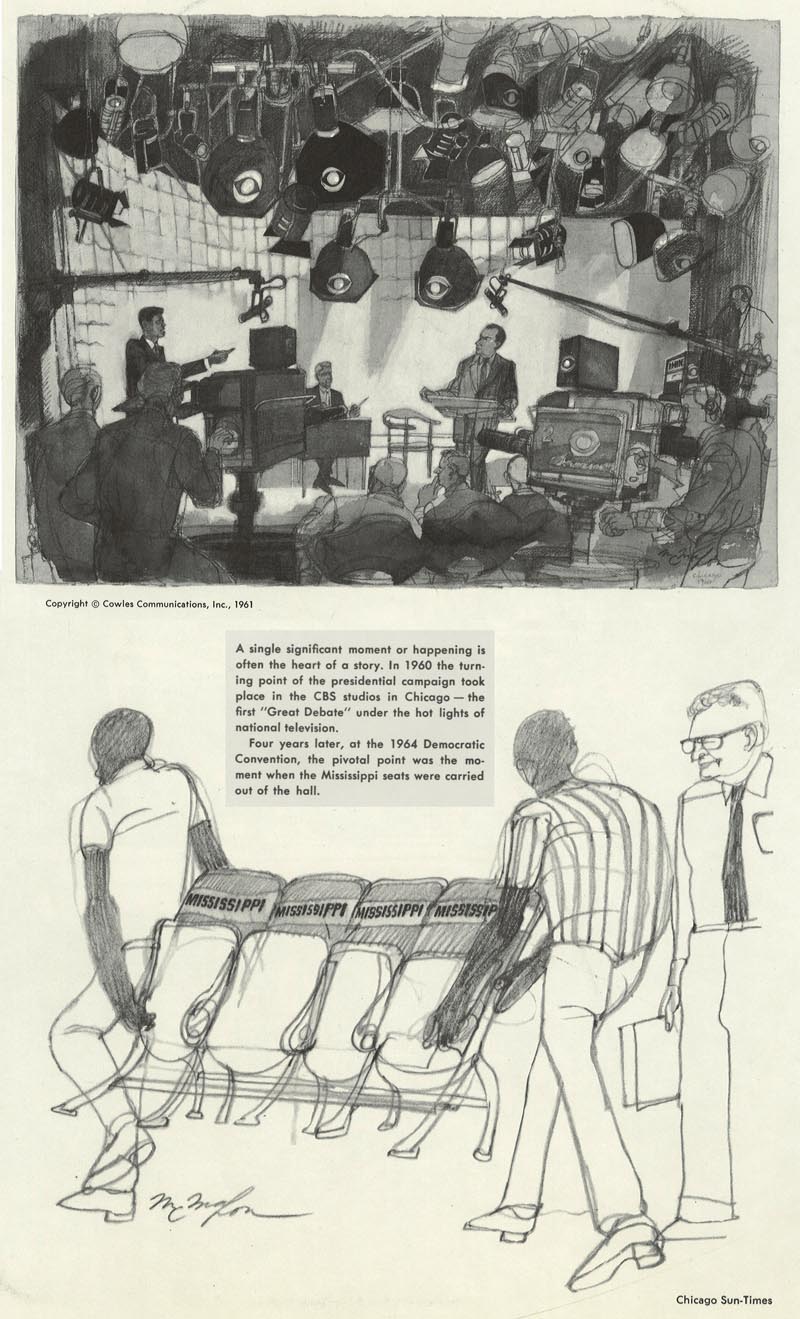

(Below, McMahon art from another courtroom reportage assignment for Life magazine, from the 1957 NYAD Annual)

FAS: How can an artist break into the sort of reportage you do? After all, you have the contacts, the reputation and the resources to finance these exploratory trips.

FM: Not every artist will want to go to India or be interested in the Common Market. A guy could work for his local newspaper. There are companies in his area who might want to do an annual report. Regional and local advertising agencies might give him assignments. He should be observant. You ask yourself, "How does this look?" Not many have really done this.

FAS: Do you ever paint for pure pleasure or make a fine arts painting instead of something to sell?

FM: I don't see much difference between work done for publication and work done for galleries and museums. This is my serious work. There's too much talk today about divisions in the arts between commercial and noncommercial, about one as serious and the other as nonserious art. Most great artists in history were commercial artists - they earned their keep by painting for their patrons. I can't work today for Philip II but I may do commercial work for Container Corp. of America of McDonald's Hamburgers.

FAS: You have managed to "do your thing" and be rewarded for it. But clients seek you out because of your individual approach. What advice can you give the artist who is not yet firmly established and who must do what the client wants but also wants to express his own point of view and approach?

FM: He should do his job the way they ask for it but try to go beyond what's asked because they never ask you to do what you're capable of doing. They don't know what you can do. The artist can see things others can't. Do what's asked - but always do something for yourself as well.

* Many thanks to Matt Dicke, who provide most of the material for this week's posts.

Post a Comment